The Signal Revolution – From Narrative to Nowcast

UX discourse is currently living through a paradox. At the same time that talk of better customer experience, AI-assisted design, and data-driven decision-making is accelerating, genuine understanding of the human being seems to be drifting ever further away. The problem is approached by adding tools, metrics, and intelligent systems, even though the foundation on which these solutions are built is already fractured.

In this article, I argue that UX does not need another version, an upgrade, or more advanced technology. It needs to be dismantled. Contemporary UX thinking rests on an ontology in which the human being is understood as a rational actor moving along a two-dimensional path. When this assumption is false, every solution built on top of it – including artificial intelligence – only accelerates the production of erroneous conclusions.

This is not a question of design, interfaces, or even technology. It is a question of how the human being is understood in the first place.

UX 2.0 Is the Wrong Answer

Talk of “UX 2.0” or “AI-driven design” is appealing because it promises continuity. It creates the impression that the current way of thinking is fundamentally sound and merely requires more powerful tools. This is a false premise.

The core problem of UX is not that interfaces are poorly optimized or that there is insufficient data. The problem is that the entire model assumes the human being acts linearly, rationally, and independently of context. When artificial intelligence is added to this model, the result may be more analysis, but not better understanding.

Adding tools to a flawed foundation does not fix the problem. It merely makes the errors more systematic and more convincing. UX 2.0 is the wrong answer because it responds to the wrong question.

The Line Is a Lie, the Vector Is the Truth

At this point, it is necessary to be mathematically honest. The linear user journey is a line. It describes movement from point A to point B. It assumes a single direction, a single goal, and a single measurable dimension. This is a simplification that does not correspond to human reality.

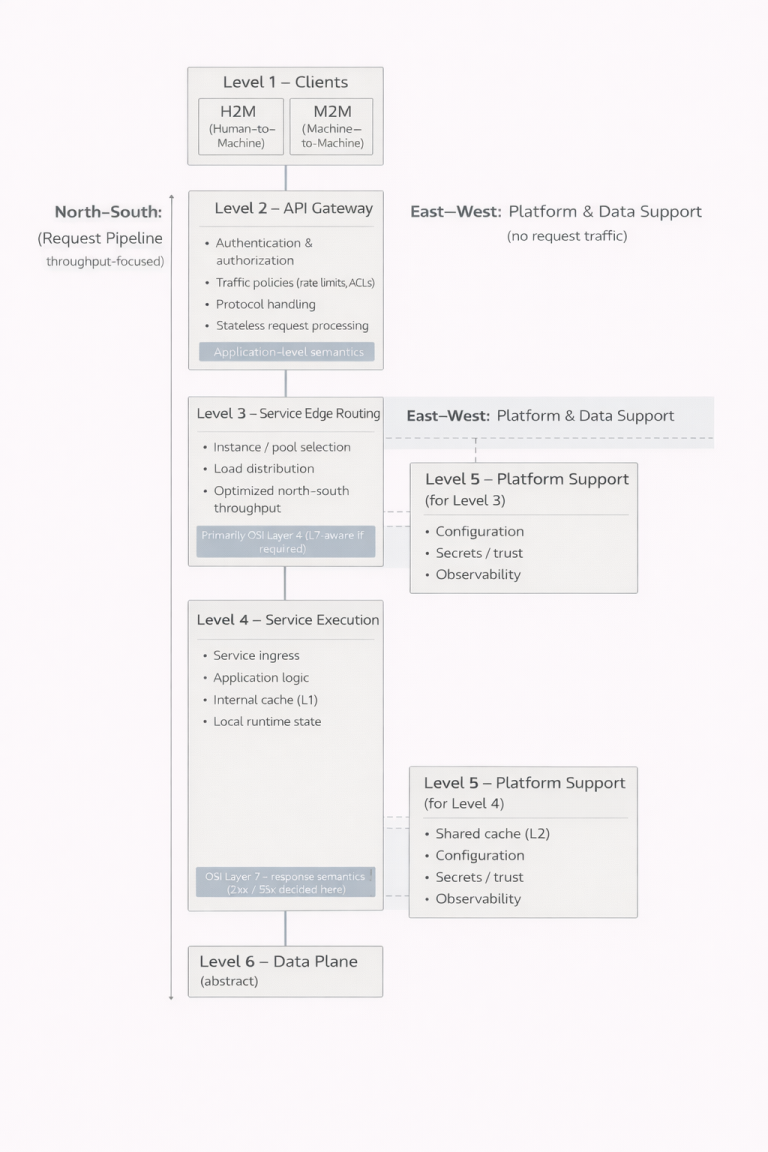

Actual experience is not a line but a vector. It has direction, magnitude, and context. A person does not move through a system merely by progressing forward, but by reacting, hesitating, adapting, and becoming overloaded across multiple dimensions simultaneously. Experience unfolds in a multidimensional space, not on a two-dimensional map.

In this article series, this is referred to as a dynamic state, zt. It is not a number on a scale from one to ten, nor is it a single data point. It is a momentary state shaped by physiological tension, cognitive load, and environmental noise. This state changes continuously, often faster than any narrative model can describe it.

When UX relies on lines, it lies to itself. It depicts experience as it is hoped to be, not as it actually is.

Traditional UX attempts to describe experience as a single number – a scalar. One value, one direction: satisfied or dissatisfied, successful or unsuccessful. NPS, CSAT, and similar metrics assume that experience can be condensed into a single quantity that can be compared across time and users. This is not merely a simplification; it is a fundamental error.

Human experience is not a scalar. It is a vector. It has intensity, direction, and contextual orientation. Two users may give the same score and yet be in completely different states. One may be adapted, another exhausted. One may be rushed but accepting, another irritated but still functional. The scalar erases this distinction entirely.

When we measure experience with a single number, we measure magnitude but not direction. We do not know where the person is moving, what is loading them, or what is releasing capacity. A vector, by contrast, contains this information. It does not ask only how much, but in which direction and with what force.

For this reason, “the vector is the truth” is not a metaphor but a precise claim. The problem of UX is not that its metrics are imprecise, but that they attempt to describe a multidimensional, dynamic state as a simple line. This is like trying to understand motion solely through speed, while ignoring direction, resistance, and external forces.

When reality is vectorial and measurement is scalar, blindness is inevitable. And it is precisely on this blindness that traditional UX thinking is built.

From Narrative to Nowcast

UX has traditionally been built on narratives. User journeys, personas, and customer paths are stories about what is assumed to have happened. They are constructed retrospectively to rationalize complex reality into a manageable form.

Nowcast thinking begins from an entirely different premise. It does not ask what happened or what is likely to happen, but what state the human being is in right now. It does not attempt to explain the past or predict the future, but to observe the present.

This shift from narrative to nowcast is the true rupture within UX. It requires abandoning stories and focusing on signals – not because stories are false, but because they are slow. Experience unfolds faster than language.

The Interface Is Only a Symptom, the System Is the Disease

In recent years, the UX field has narrowed itself in a way that can justifiably be called self-destructive. Customer experience has been reduced to interface optimization, even though the real problems emerge at the system level.

Experience does not arise from how a view looks, but from how the system’s total forces – friction, latency, demands, and ambiguity – intersect with the human being’s momentary tolerance. An interface can be visually flawless and still impose significant load if the system as a whole operates against the human.

When UX focuses on symptoms, it leaves the disease untouched. This is not the fault of individual designers, but a structural consequence of an incorrect model of the human being.

This Is Not About Design, but About the Human Model

At its core, the UX crisis is philosophical. It does not concern only products or services, but the way human beings are understood within systems. When the human is treated as a static component, systems are built that fail to recognize stress, context, or human limitation.

This way of thinking is not confined to commercial services. It is visible in media, governance, and decision-making. When humans are treated as averages, deviations are interpreted as disturbances. When systems are optimized from the perspective of process, lived experience becomes secondary.

In this sense, the UX crisis is also a societal crisis. When we stop seeing the human, we begin optimizing the system for itself.

Not a Solution, but a Map

This article does not offer a solution, nor is it intended to. UX Is Broken is not a framework you can download as a PDF or deploy in a sprint. It is a map that points away from linguistic fictions toward signal-based understanding.

Real change does not emerge from better design, but from an ontological shift. Away from narratives, away from lines, and away from averages. Toward dynamic states, intensity, and momentary reality.

In the next – and final – part of this series, the question will no longer be how we measure or model the human, but how organizations and leadership change when we stop lying to ourselves.